System Change Not Climate Change Conference 2006

Panel discussion with four invited speakers, then open for debate.

Panel discussion with four invited speakers then open for debate.

The End of Suburbia

The Greening of Cuba

System Change Not CLimate Change: OUR TWO DEMANDS- (a)Beyond Kyoto- 90% reduction in greenhouse gas (b)Frequent and fare free public transport now. PLEASE HELP US AND DONATE TO CLIMACTION- KIWIBANK a/c number 389005 094861900. Contact us at 021 186 1450

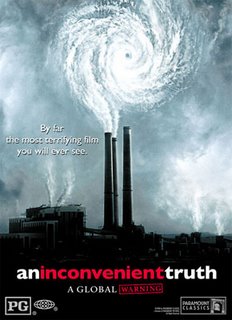

AL Gore! What’s the score?

The System’s Rotten to the Core!

Leader of Green Party and Mayor of Waitakare first to sign Climaction Petition.

Al Gore paid a fleeting visit to Aotearoa, meeting with a handpicked audience of NZ’s corporate and political elite at

(Audio at http://xtramsn.co.nz/news/0,,11964-6563186-300,00.html )

Instead, the first signatories of Climaction’s Free and Frequent Public Transport Petition were Green Party Leader Jeanette Fitzsimmons, Residents Action Movement Councillor Robyn Hughes and Mayor of Auckland’s Waitakare City Bob Harvey. Thousands more signatures will be gathered by Climaction over the next month- you can add your moniker online at www.climaction.blogspot.com

(Any suggestions? Contact the blog at solidarityjoe@yahoo.com )

The Climaction Carnival on Sat Nov 4th was a big success, attracting a core of 300 people on the day, with many more taking part. The flagging of Civil Disobedience publicly on the day saw a climb-down from both police and possibly Auckland Council, in that 5 minutes before we were due to move onto the street, the cops offered to block the whole road off for us. They had a look at the numbers we had brought and the determination of the organising crew and made a decision to concede, possibly under orders from Auckland Council who had made a political decision of non confrontation. It was a major victory for advertising the location and our tactics, that just days beforehand were being questioned by both mainstream reformists and black bloc enthusiasts. So round one to Climaction in the battle for the streets. This will strengthen our non conspiratorial, democratic calls for mass direct action in the future.

The People's Assembly held around a ton of melting ice was also fantastically dynamic, with both Auckland Regional Councillor Robyn Hughes and Elaine West from RAM speaking strongly in support of Climaction's demands for Free and Frequent Transport and a 90% reduction in greenhouse gasses by 2030. Climaction hegemonised the debate; challenging Councillor Christine Caughey (Action Hobson) and Auckland Regional Council transport committee chair Joel Cayford whether they both supported RAM’s free buses policy. Councillor Caughey said she did, with Joel Cayford saying yes in principle but how was it going to be funded? A later vote at the Assembly resolved by a huge deafening majority that it should be funded not by taxing ordinary workers, but taxing the rich and the corporations. RAM’s free buses song “Moving On” sung by our own Roger Fowler went down a storm as it wrapped up the assembly- totally behind Climaction’s demands in the city.

The Union input into the People’s Assembly was also something mainstream environmentalist protests had not seen before- there were banners and reps there from the SFWU, NDU, EPMU, Unite and Solidarity. Fala Hualangi, the SFWU organiser leading the CleanStart campaign in the city for cleaners, spoke eloquently about the fate of her native

The other noticeable thing about the People’s Assembly was it’s wholehearted support of the word “Revolution” as synonymous with the slogan “System Change not Climate Change”- Revolution was used as a political term unapologetically, confidentially and joyously by speakers as diverse as myself (Joe Carolan) from Socialist Worker , Simon Oostermann from the NDU, John Darroch from Radical Youth, and a woman called Josie in her 70s who made a beautiful speech at the end of the Assembly, saying that climate change would effect everyone on the planet regardless of race, gender or age, and that she would support a revolution to stop it. This got a huge roar of joyous applause from an audience not really expecting this from a woman in her 70s, but revolution is an infectious thing, and I had guessed from talking to her earlier she would make a dynamic and surprising wrap up. Not since the heady days of the early anti capitalist movement of 2000-2001 have I seen an openness on the left to discuss anti capitalism and revolution as openly as this.

The day was also a great carnival and celebration- the music was rocking, with anthems of struggle and resistance echoing across an occupied

Mick Jagger’s “Street Fightin’ Man”, Public Enemy’s “Shut em Down”, John Lennon’s “Power to the People”, Lindon Kwesei Johnson’s “War ina Babylon” and the Manic Street Preacher’s “Masses Against the Classes” providing a backdrop for the snowball fights, tobogganing, chalking, dancing, football, break dancing, samba, sunbathing, picnicking and networking going on in the middle of the street. Andrew the Polar Bear sat on a ton of melting ice, Food Not Bombs fed the masses, colourful banners and flags flew in the sun, and 45 new people joined Climaction. The Call Out to Al Gore next Tuesday should attract a good crowd too provided we do our media work well- last Saturday we got coverage from TV3, a picture in the Sunday Star Times and a write up in the Herald OnLine- Next Tuesday could be internationally significant if we play our cards right.

Climaction has attracted a new layer of supporters and potential members, some of them extremely committed and energetic activists. We have built a comradely and fiercely democratic culture that looks to mass direct action in the tradition of Martin Luther King. Climaction has imagination, daring, a cool level head under pressure but looks to mass, direct action and revolution as the only viable solutions to the ecological crisis of the 21st Century.

Interview by Andrew Stone, October 2006

Governments and big business clamour to show their green credentials but their 'solutions' fall way short of what is necessary. George Monbiot talked to Andrew Stone about his new book, Heat, and the more radical policies he believes are essential.

George Monbiot does not start Heat, his prospectus for fighting climate change, with melting glaciers or parched soil. He begins with the metaphor of Faust, the 16th century cautionary tale popularised by dramatist Christopher Marlowe in The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus: "Faust is a man who swaps the long term for the short term," he tells me, "in order to have 24 years of indulging himself to the absolute limit. He strikes a deal with the devil. He can get whatever he wants now, in return for eternal damnation. He refuses to believe that eternal damnation is a reality.

"Now, I'm not saying that climate change is eternal damnation, but it is a massive long term problem, which we are currently trading for a few decades of 'pleasant fruits and princely delicates', to quote from Marlowe. Like Faust, for a few earthly delights we are sacrificing the well-being of the biosphere for at least a couple of hundred years, probably for a lot longer.

"It's just not worth it. The pleasures we have extracted - such as bigger and faster cars, more and more junk to throw in the landfill, and food brought in from further and further afield - are not fundamental components of our well-being, and yet we're trading them for fundamental components of our well-being in the future."

The metaphor, fleshed out in greater detail in Monbiot's book, seems remarkably apt. Monbiot's ability to communicate complex ideas accessibly have made him a popular columnist and speaker for the environmental and global justice movements. He needs these skills in Heat to take the reader through a maze of complex and often contradictory economic and physical calculations. His aim? To prove that Britain can make 90 percent cuts in its emissions of carbon dioxide (the leading greenhouse gas) by 2030.

I ask why such a huge cut, when the Kyoto agreement only called for an average 5.2 percent cut by industrialised nations. "The Kyoto figure bears no relationship to any scientific assessment of what needs to be done. It was entirely a matter of political convenience. The purpose of Kyoto was to get some sort of figure on the table and to get some kind of action. But it's only a very small fraction of where we need to go.

"As the biosphere's ability to absorb carbon declines, and as the human population rises, just in order to stay where we are in terms of our total carbon emission and its relationship to the natural world, we need a 60 percent cut, which means a 90 percent cut in the rich nations."

This unequal cut emerges from the fact that carbon emissions per person are many times higher in Britain than in the poorer countries that will tend to suffer first and hardest from climate change. As a result, the model of contraction and convergence has gained widespread recognition. It proposes that each person in the world is allocated the right to pollute a set amount. The allocation would need to begin much higher for those in the more profligate richer countries, but would rapidly contract until it converged with that of the poorer countries.

This equitable proposition is less contentious than the method of achieving it. Much has been made of the potential for creating a market in emission allocations. Monbiot explains why the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme has set such a poor precedent: "It's founded on a great injustice, which is that the right to pollute, which should be fairly distributed among all the people in the world, has been given in big chunks to corporations. They were just handed an allocation which reflected the amount of pollution they had produced in the past. So instead of the polluter paying, in this case the polluter was paid. The more pollution they had caused, the bigger their allocation, so some of them have done very well out of it.

"The scheme can only work if at the same time you have a commitment to cutting emissions across the economy. It's simply a tool - by itself it's not a mechanism for reducing emissions." And perhaps quite a counterproductive tool, I suggest, given that the "hidden hand of the market" has done so much to create the problem. "Exactly. It's this mystical faith in market forces' ability to do everything, even reversing problems that it has caused in the past. There's this sense that we'll leave it to the market because it's terrifically convenient. But unless the government is prepared to create a framework within which those markets function then it's just not going to work at all."

Monbiot's alternative proposal is for a system of carbon rationing. While not rejecting the market outright, it more closely circumscribes its privileges. "It starts from the presumption of fairness - that everybody gets an equal ration. The corporations aren't given the rations that belong to us. Because carbon emissions are very closely correlated to income, the poorer you are, the more money you are likely to get from that system, because the more surplus ration you are likely to be able to sell on. So there's a redistribution of wealth built into the system, which is very important. If it's done through taxation, for example, the rich can just spend more money. They can just drive their Ferraris as far and as often as they want, because they can afford to do it. It's only the poor who won't be able to do it, because they'll be stung by the taxation.

"Eco-taxes have the potential to be very regressive. They don't always have to be, but you have to organise them very cleverly if they're not going to be. But a rationing system has fairness built into it. It's also very good for concentrating the mind. You've got this certain amount of carbon and you've got to decide how you're going to use it. You've got the freedom to choose how you use it but you know that if you're going to drive a Ferrari you can't heat your house."

Big business is fond of telling us that energy efficiency is the answer. Heat details why a mixture of empty corporate bombast and lack of politics combine to make their claims hollow. "While some people have been claiming that you can do the whole thing through energy efficiency, that's simply wrong. For example, across the whole housing stock, between now and 2030 about 30 percent cuts are possible. Because so many of our houses are so badly built, this can't be remedied beyond a certain point."

But significant potential does exist. "In other areas, for instance surface transport, there's a huge scope for energy efficiency. You can't get a 90 percent cut through efficiency measures alone - that obviously requires a change in the mode of transport - but there's some very big scope for efficiency there."

Green shibboleths

However there is a phenomenon, intrinsic to the drive for capital accumulation, which means that market-led energy efficiency could actually exacerbate the problem. Sounding more like a sci-fi cartoon than an economic theory, the Khazzoom-Brookes Postulate builds on the 19th century observation of Stanley Jevons that decreasing the amount of coal needed to produce iron led to an overall increase in iron production. Since then, the world's energy efficiency has improved by about 1 percent per year. Yet our fuel consumption, with one or two blips, has risen steadily.

"It's an extraordinary proposition - that energy efficiency increases energy usage - the reason being that it releases capital for use on more energy intensive processes because the implicit cost of energy falls.

"I have to emphasise that this is a postulate. We don't know for sure that it functions but if it does then it's another good reason why the market alone can't work. Left to the market, it means that the energy efficiency measures which companies and people might take simply free up money which they can then invest in more energy intensive processes. So the energy efficiency measures that you introduce have to be locked in place with government regulations."

Monbiot is prepared to dismiss a few green shibboleths when discussing renewable power. "We have to be honest about these things. There's no point pursuing fake solutions. Climate change doesn't brook fake solutions. It responds simply to the amount of carbon that you put out.

"Some technologies in particular - micro-wind, solar power and biofuels - have been massively overhyped, quite irresponsibly by some of the people who have been selling them. They can make only a very small contribution to solving the problem. For example, in most cases biofuels are actually worse than fossil fuels in terms of their total climate impact.

"When it comes to electricity, my favoured solution involves two things. First of all, massive off-shore wind farms, built on a very large scale right across the continental shelf. By using high voltage direct current lines you can bring the electricity in from a very long way away without losing any of it, allowing you to extract renewable power from a much wider area than using alternating current.

"The other half of our energy supply would come from carbon capture and storage, which means stripping the carbon dioxide out of the exhaust of power stations and piping it away into salt water aquifers under the seabed. That technology is now fairly well established."

There are some important riders to this suggestion. Monbiot notes that regulation would be necessary to prevent carbon capture being used as a stalking horse for further fossil fuel extraction. "The coal industry loves the idea of what it calls 'clean coal'. It thinks that just because one part of the process is being sorted out, the whole process is then acceptable. Huge opencast pits, built around people's communities, are not acceptable under any circumstances."

Heat is very attentive to the relative market costs of energy. I ask Monbiot if there is a danger of losing sight of social costs and benefits. "Of course we have to take into account the fact that all costs exerted by any form of energy are not just costs which can be measured on a balance sheet. But it is important to make sure that the sources of energy we call for are as cheap as carbon resources, simply because our money then goes further. Solar panels are many dozens of times more expensive than producing energy from on-shore wind. So if you are faced with a choice of using £1 billion to install solar panels, or £1 billion to install wind turbines, you should go for the wind turbines, not the solar panels.

"However, there's no doubt that you've got to take into account all sorts of other issues as well. In that case you have to take into account that a lot of people very strongly object to having wind turbines put in scenic areas. But you have to have good value for money if you're going to have any hope of persuading people that it's worth investing in alternative energy."

We move on to another thorny issue - how to get people to drive less.

"This is a big problem. Technologically, it's incredibly easy to solve. In the book I champion the coach system proposed by economist Alan Storkey. At the moment, coaches are appalling. They're incredibly slow, a deeply depressing experience. You're made to feel like a third class citizen. They trundle in and out of the city centre, which is just insane.

"You need to have coaches which stick entirely to the motorways, with coach stops on the motorway junctions, linking up with public transport from the city centres. It could be an extremely fast, efficient and comfortable service, with coaches on dedicated lanes on the motorways, given priority at traffic lights. They would actually be moving faster than the cars on the motorway.

"I accept that there are many things that people enjoy about driving their car. But I think that when they see coaches whizzing past them on the inside lane when they're stuck in a traffic jam, they're going to wonder if it's worth it. When they see that people in coaches will be able to watch films, work on their laptops, sleep, eat and drink, a lot of people are going to see that travelling by coach is a superior option."

Monbiot admits that he has been less successful in proposing a substitute for the fastest growing source of emissions - aviation. "I became so desperate that I even contemplated airships," he laughs. "Of all the possible solutions, that might be the best one if we're to keep flying, however improbable it sounds.

"There are no good technological substitutes. Richard Branson is now saying that he's investing £1.6 billion in alternative fuels and technologies for aviation. Well, if indeed that's what he thinks he's doing, he's wasting his money. Those alternatives do not exist. There are a very narrow range of conditions which allow flight. There's no foreseeable alternative to the jet engine at the moment; there's no foreseeable alternative to kerosene as jet fuel. I'm not saying that will always be the case, but we have to deal with the problem of aviation right now. The only way of dealing with it is by grounding most of the planes which are flying today."

One proposed method for achieving this is to levy aviation fuel tax. Some campaigners argue that such green taxes would drive up the cost of flying and so reduce its frequency. Monbiot resists this argument: "I'm not too keen on taxation as a method anyway, because I think that carbon rationing is much fairer, and it's much less punitive for the poor. But in particular, aviation fuel tax is just a non-starter. You'd have to unpick 4,000 bilateral trade agreements linked to the 1944 Chicago Convention, and that's simply impossible in the kind of timescale that we're talking about."

A tax on aviation profits would probably be preferable, but I am disturbed by the second part of Monbiot's explanation. For the kind of economic restructuring climate change requires we are going to have to tear up some rule books. Monbiot is one of the foremost critics of world trade rules, and their devastating effect on the world's poor. But his logic of creating a carbon economy inside the existing one risks accommodating the latter for the sake of the former.

Even the best metaphor will only illuminate some features for comparison. Seen as a cautionary tale for humanity personified, the Faust metaphor works. But it cannot encompass the contradictions within humanity - between the tiny minority who direct the world's economy and the rest of us. But when I ask Monbiot about the corporate disinformation campaign of the "climate sceptics", you would think we were all equally culpable for climate change:

"One of the reasons why companies like Exxon have been so successful at persuading us that climate change isn't happening is that we want to be persuaded - we don't want to believe it. Just like Faust, who said, 'Thinketh thou... that, after this life, there is any pain? Tush, these are trifles and mere old wives' tales.' We are exactly the same. We want to be fooled."

While Heat is principally a demonstration of what is possible, it does conclude with an appeal to campaign. Disappointingly, its point of reference is the small environmental protests of the 1990s rather than the anti-war movement. Still, Monbiot is clear that "we need to launch the biggest popular campaign that the world has ever seen". Unfortunately, his emphasis on our psychological denial persists. "We need to persuade governments that if they opt for controlling climate change they will not be unpopular as a result - in fact the people are behind them. At the moment governments can be quite complacent about this, because they know that we want them to pretend to act. We don't want them to actually do what needs to be done - we want them to pretend to do what needs to be done."

It will require austerity, says Monbiot. "It hasn't happened very often in the past," he laughs, and thinks of a chant: "What do we want? Less bread!"

Capitalists need to constantly create new markets, for which they have to create new needs and desires. Monbiot argues that "this constant growth of the amount of goods and services available is just totally unnecessary for our quality of life. And it begins to reduce our quality of life as well. As more and more roads are built, as more and more airports are built, life becomes less and less peaceful and pleasant. In the rich countries we've got quite enough of everything already, if only we distributed it properly."

That prize, of ridding ourselves of atomised communities and alienated working lives, is a worthy one we will need to combine with the fight to save the planet. But I think we need to work on the chants.

http://www.socialistreview.org.uk/article.php?articlenumber=9843